In the room, five famous artists from around the world, who have come to this room of sculptor Grybas from various periods and countries, are together discussing a unique case in the history of the city of Kaunas: have you ever heard of the wrong monument being erected? Indeed, such a case occurred in Kaunas in 1990—we erected the wrong monument to Vytautas the Great!

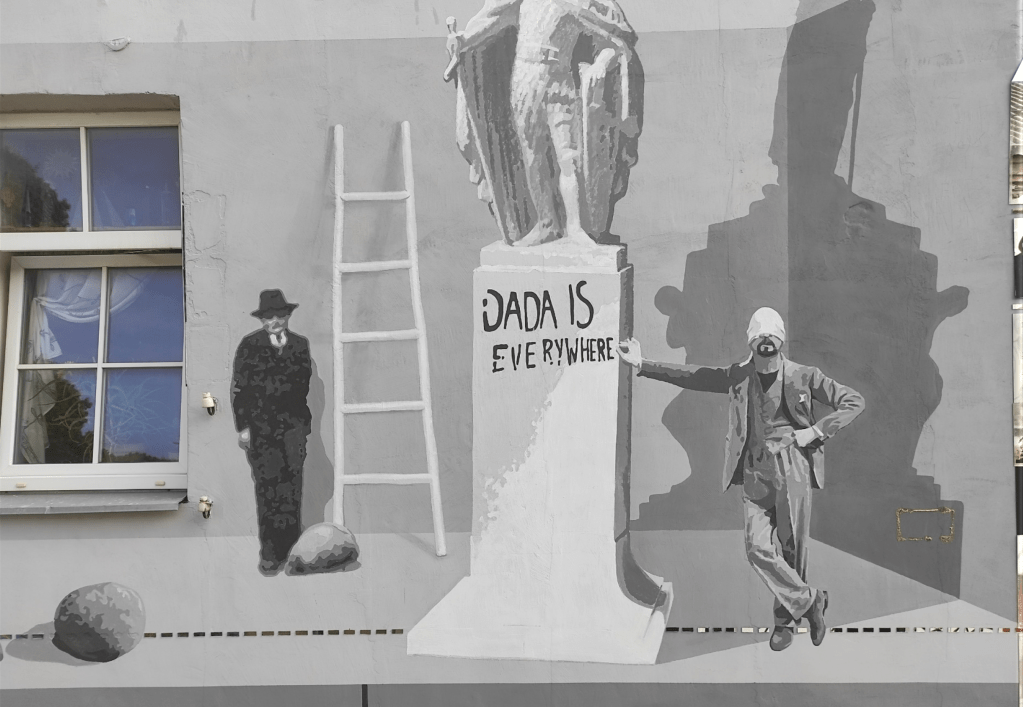

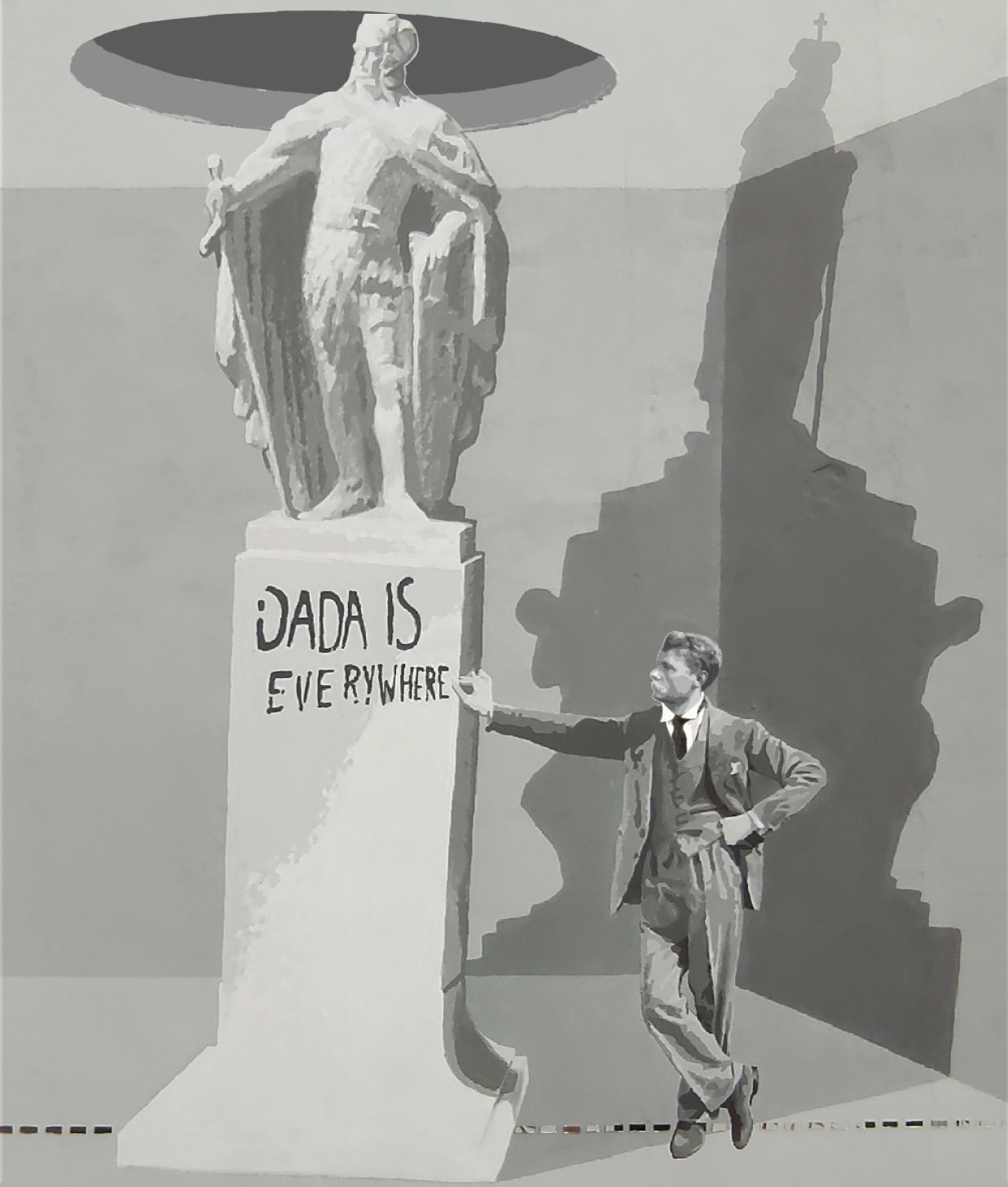

Artist Vytenis Jakas, in the Yard Gallery’s fresco cycle “Rooms of Secrets” in 2022, created the fresco “Relics of the Battle of Grunwald,” which is a visual fragment reconstructing V. Grybas’s letter. The monument to Vytautas the Great in the fresco is authentically restored—as it was originally created without distortion in 1930 by Vincas Grybas. The sculptor is depicted in the fresco with his eyes covered because we, during various historical periods, have covered his eyes, wanting him to believe in what he himself did not create. His covered eyes also symbolize ourselves, who, with wide-open eyes, do not dare to look at our own history. On the pedestal of the sculpture, the inscription “DADA IS EVERYWHERE” is drawn, thus reminding us of the signs that both youngsters and true artists scribble on the walls of city buildings, as if connecting the monument with the modernist art spirit of Western Europe and the whole world. On the sculptor’s covered eyes falls the shadow of the current sculpture of Vytautas the Great standing in Laisvės Alėja, with the previously discussed imposed bas-reliefs of allied soldiers casting their shadow.

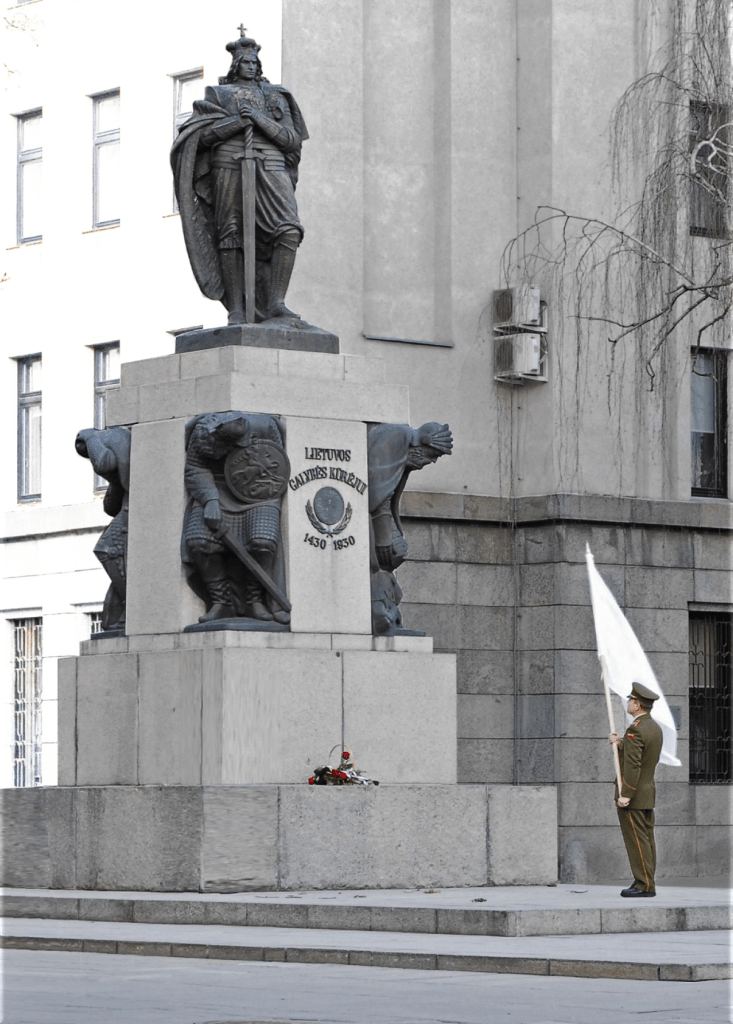

And yet, the problem is not the monument itself; the problem is its inappropriate display location and the fact that, in our haste, without delving into the pre-war context and sculptor V. Grybas’s original proposal, in 1990 we erected not the right monument to Vytautas the Great.

This monument, supposedly dedicated to commemorating the Battle of Grunwald, actually contradicts historical truth. Stories about who won the Battle of Grunwald do not match even today…

Pay attention to the four nations kneeling under Vytautas’s feet. Were they obedient servants of his might—or allies? This suggests there is another story here that we did not know when restoring the monument in 1990…

Why was the monument to Vytautas, in 1932, erected in a military unit and not on Laisvės Alėja?

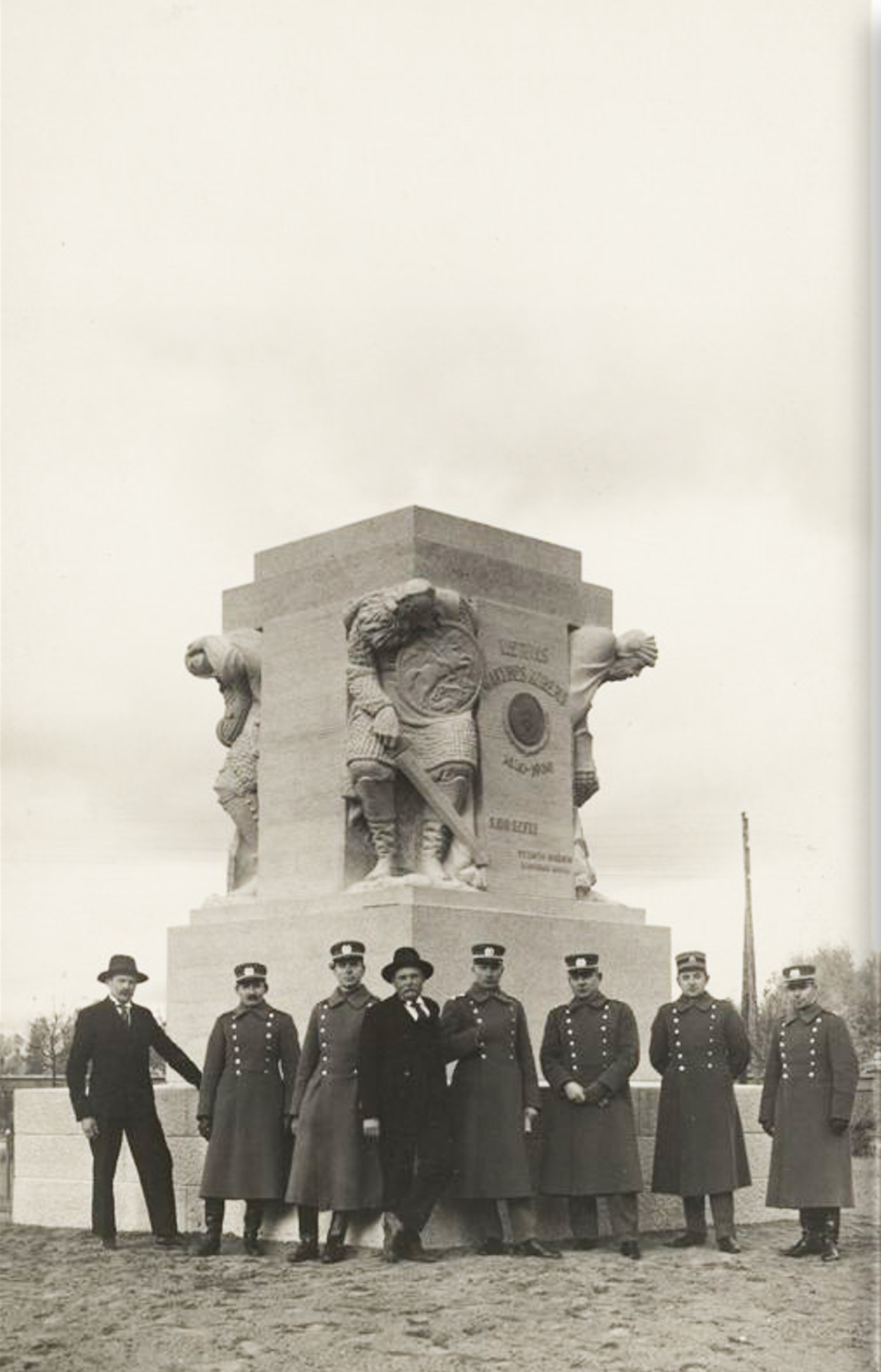

Answers to these and other questions can be found by looking more closely at the pre-war context. Here, I would like to briefly mention that the monument to Vytautas the Great, restored in 1990, is a copy of the monument commissioned by the Lithuanian Military Academy, which stood in Aukštoji Panemunė (later demolished). The monument to Vytautas the Great created by sculptor V. Grybas before the war was intended to educate and inspire soldiers for an important campaign—the liberation of Vilnius. The interwar monument was designed to prepare soldiers for battle according to a certain military methodology and was created to stand in a closed military territory, i.e., it was not intended for public display.

Let that other sculpture remain in the shadow of our history, and let the sun, falling on the main monument at the appropriate time of day, highlight its path to truth and its connection with both contemporary art and the spirit of today.

Dali, Magritte, and Duchamp, who are visiting Vytenis’s room, bring along their own secrets. In the room on the left, a guest settled in a peculiar, though probably comfortable, pose has his own secrets… a cloud, a shadow standing behind him… This is one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, Marcel Duchamp—by the way, an avid chess player—who is curiously exploring the unique case of Kaunas city history. Since he could not stand artists and museums, art dealers, and exhibition openings, he would likely appreciate the Yard Gallery environment, saying during his visit his famous phrase: “A work of art doesn’t exist on its own; works are created by those who look at them.”